Yes, AI is affecting employment. Here’s the data.

August 26, 2025

Artificial intelligence is both old and new. Old in that its founding principles and techniques have been around since the 1950s. New because the technology has continuously reinvented itself ever since.

Its latest iteration, in the form of generative AI, delivers an ability to create content, summarize documents, analyze data, and sift through vast amounts of digital information.

Generative AI was introduced to a broad consumer audience in 2022 with the launch of ChatGPT and other consumer-friendly tools. Since then, policymakers, academics, workers, and employers have shown growing interest and raised bigger questions about AI’s impact on jobs.

Last year, ADP Research found that technology was starting to affect the labor market. In January 2024, the United States employed fewer software developers than it had six years earlier.

This week, Dr. Erik Brynjolfsson and his team of researchers at the Stanford Digital Economy Lab add dramatic layers of additional information with their new paper, “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence”.

Using granular, high-frequency ADP payroll data, Stanford’s team observed the occupations, tasks, and employment of millions of workers at thousands of private companies. They found a substantial decline in employment for early-career workers in occupations most exposed to AI, such as software development and customer support.

Overall employment for AI-exposed jobs is up but for young workers it’s falling

Brynjolfsson and his co-authors began by categorizing jobs according to their exposure to AI. In jobs with high AI exposure, employment for 22- to 25-year-olds fell 6 percent between late 2022 and July 2025.

In contrast, employment among workers 30 and older grew between 6 percent and 13 percent in that same category of jobs.

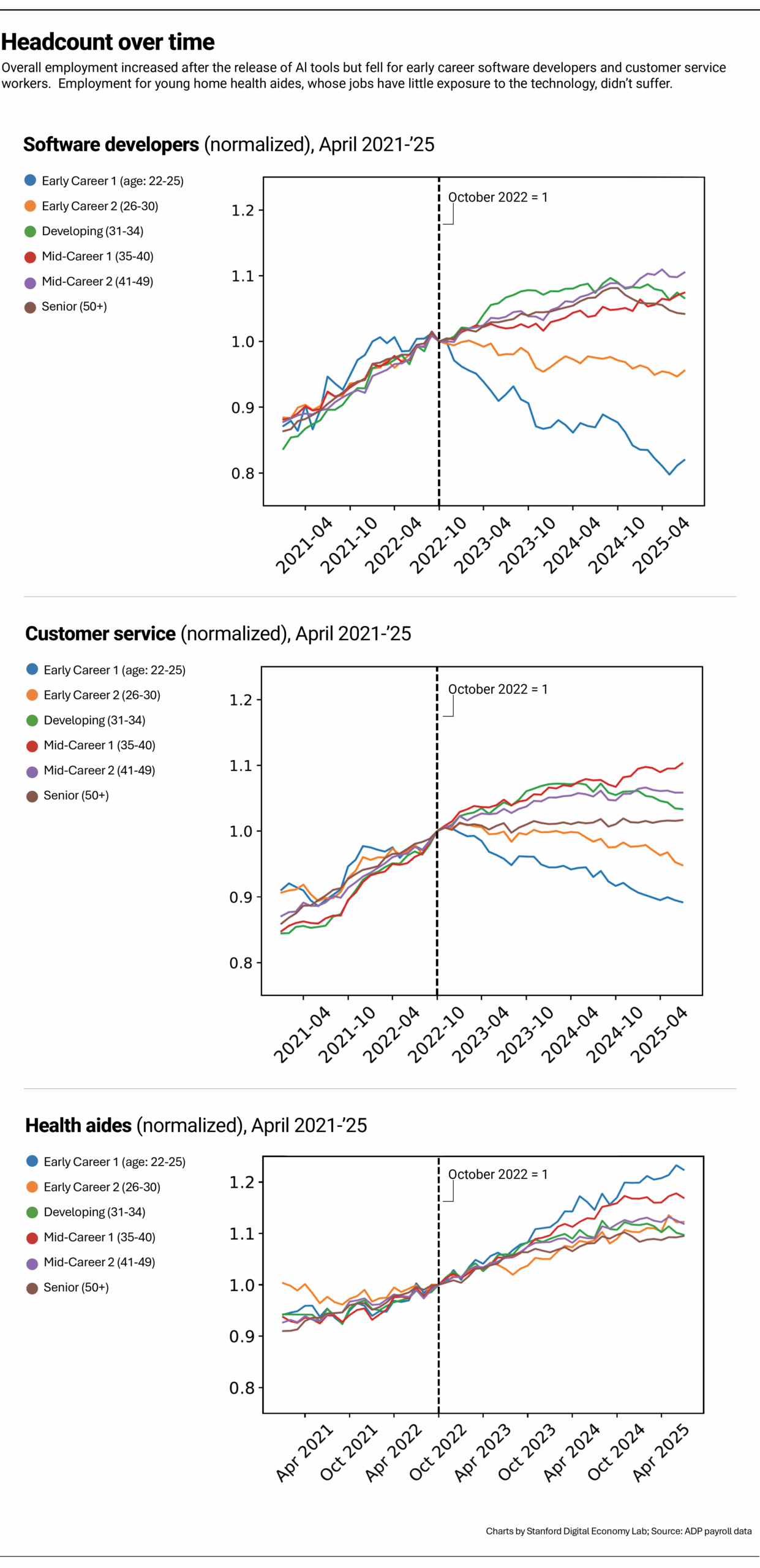

To illustrate this finding, Stanford looked at software developers and customer service providers, two occupations with high exposure to AI. The researchers also examined health aides, whose jobs are less exposed to AI technology.

They found that in July 2025, employment for the youngest software developers was 20 percent below its late fall 2022 peak. A similar pattern held for early career customer service workers, whose employment in July 2025 had fallen nearly 11 percent from its peak in November 2022.

During this time period, employment in both occupations was mostly flat for workers aged 26 to 30 and it grew for those aged 31 to 24. Employment also was up for mid-career workers aged 35 to 49 and the oldest workers, those 50 and older.

The story was different for health aides, whose jobs have little exposure to AI. For this occupation, employment was up for all age groups.

Employment for early career software developers and customer service workers fell dramatically after the release of AI tools, but employment for young home health aides, whose jobs have little exposure to the technology, were unaffected.

The type of AI matters

AI can affect jobs in two ways. It can do tasks that people typically do, such as answering calls and programming code, thereby displacing the worker. Or it can augment work, helping people do their jobs faster and better.

Stanford researchers tested the impact of these two forms of AI by segmenting AI tools into two groups, those that automate work functions and those that augment them.

They found that early career workers in roles with tasks that can be easily automated are most vulnerable to AI.

My take

Last week I attended the Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole economic symposium. The theme this year was labor markets in transition, and the economists and central bankers in attendance dug deep into models and data on a range of megatrends, including fertility rates, worker mobility, and labor force participation.

No one presented a paper on AI, yet the technology shadowed every presentation and discussion. Over the worker lifecycle, as occupational tasks become more complex and harder to automate, AI tools tend to augment rather than replace work.

Brynjolfsson’s new paper identifies which jobs are vulnerable to AI and which are positioned to gain from it. The research also sheds light on the potential of AI to empower tenured workers. It’s powerful knowledge that can help employers and policymakers transition young workers into careers and skills that stand to benefit from the AI-driven productivity boom ahead.

The week ahead

Monday: New home sales started the week with a continuation of the downbeat trend that has characterized the 2025 housing market. In July, the number of signed contracts on new single-family homes fell 8.2 percent from a year ago, Census Bureau data showed.

Tuesday: Are consumers still buying expensive big-ticket goods? Durable goods will be a tale-tell sign from the Census Bureau. And speaking of big-ticket items, June home prices from the S&P Cotality Case-Shiller Home Price Index will be a telling indicator of the current status of housing affordability.

Thursday: We get an updated read on economic growth for the second quarter from the Bureau of Economic Affairs. This report is backward looking but will give economists plenty to chew on.

Friday: The week’s headliner comes at the end, when the BEA releases the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation. The PCE, along with the August employment report, are likely to be the key drivers of any Fed move on interest rates.

This post was updated Oct. 6, 2025, to correct employment data on career customer service workers.