Where have all the workers gone?

June 17, 2025

Every now and then, it’s worth taking a break from rapidly changing economic developments to focus on long-term trends affecting the world of work.

One long, slow change we’ve been living through for years is the evolution of labor market participation in the United States.

The unemployment rate grabs most of the attention every month as an indicator of the health of the labor market because it tells us how easy—or difficult—it is for people to find jobs.

The labor force participation rate—the share of people 16 and older who are working or actively looking for work—has a different message. It’s an indicator of the population’s willingness to work at current wages.

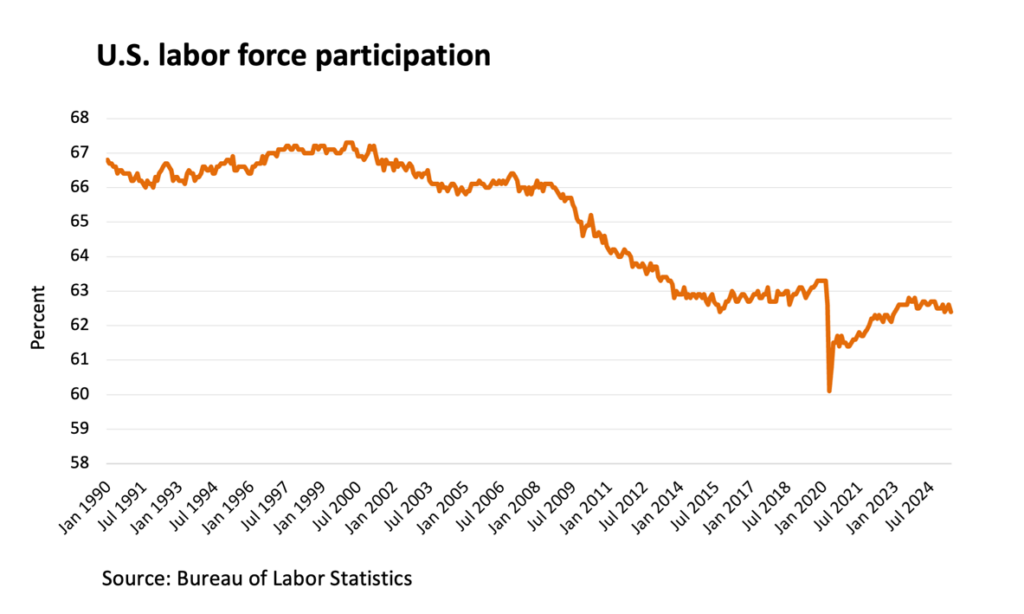

Over the past two decades, the labor force participation rate has been on a downward trajectory. In the 1990s, it was comfortably greater than 66 percent, meaning two-thirds of the working-age population were employed in a part-time or full-time job, or actively looking for one.

After the 2007-2009 recession, labor force participation declined swiftly, then stabilized at just above 63 percent. That stability didn’t last. During the throes of the pandemic in early 2020, labor force participation cratered to a record low of 60.1 percent.

More recently, the participation rate is greater than 62 percent, but still below pre-pandemic levels and well below its peak of 67.3 set in early 2000. In May, the labor force participation rate fell by 0.2 percent.

So why are U.S. workers and job-hunters becoming scarcer, and what does that mean for the economy?

The age effect

Prime-age workers, those between 25 and 54, have the greatest and most consistent participation in the labor force. In the 1990s, prime-age worker participation was more than 83 percent, similar to the levels we see now.

Participation among younger and older workers is more variable. Young people are more likely to attend college or trade schools before joining the workforce. People reaching retirement age are likely to leave the labor market. And because the share of baby boomers approaching retirement has grown more rapidly since the pandemic, this cohort effectively has reduced the overall labor force participation rate.

The wealth effect

Age and life stage variables are important. People might drop out of the labor market temporarily to attend college or raise children, or they could leave altogether when they retire.

The wealth effect, however, is more about money. As household wealth increases, people tend to work less or not at all. Economic theory suggests that wealth accumulation reduces the appeal of working and thus shrinks labor force participation.

Over the last 20 years, U.S. combined household net worth has climbed almost 190 percent, from $55.5 trillion to $160.3 trillion. Last year alone, household wealth grew by 10 percent as stock prices and home equity soared.

The downward pressure of these wealth effects on the participation rate could be easing, though. In the first three months of 2025, household net worth shrank for the first time in two years, dropping 1 percent or $1.6 trillion from the last three months of 2024.

The gender effect

In the early1990s, the participation rate among men was greater than 75 percent, about 20 points higher than labor force participation by women. Labor force participation peaked for women in the late 1990s and early 2000s at just above 60 percent but has since declined.

Currently, this gender gap has narrowed to about 10 percentage points.

The gap hasn’t narrowed because more women are now joining the workforce, though. It’s because men are leaving it. In May, the participation rate for men was 67.7 percent. For women it was 57.1 percent, about what it was in the early1990s.

As U.S. shifts to service-oriented jobs, as manufacturing and industry become a smaller piece of the pie, and as employers look for a new basket of in-demand skills, more men are opting out of the labor market.

My take

The backbone of the U.S. economy is its labor market and the workers who participate in it. In the past 20 years, a shrinking share of the working-age population has been joining the workforce.

These absences from the labor force can have many explanations. Taking time away from work for training or higher education could lead to a more productive workforce. But departures from the labor force due to retirements and the changing nature of work itself could erode productivity.

And when more people are sitting on the sidelines, it can take higher wages to lure them back in. As labor force participation has declined, year-over wage growth has stabilized at higher levels than in the past.

These powerful forces are reshaping not only those who choose to work, but for how long and for how much.

The week ahead

Tuesday: Much has been made of the disconnect between downbeat soft data as a leading indicator to more positive hard data. But consumers are feeling positive for the first time in months and inflation indicators have come in weaker than expected. The most important hard data release of the week, May retail sales from the Census Bureau, is more likely to show resilience than fragility.

Wednesday: There will be a lot to unpack in the Federal Reserve’s rate decision today, regardless of their call. One thing economists will be watching are Fed projections for the economy and whether the central bank still expects a soft landing this year. In May, the committee raised its median view for unemployment and inflation while lowering it for GDP.

Higher costs for borrowing and building are translating to higher home prices, which has made for a lackluster year for residential sales and construction so far. I’ll be watching whether Census Bureau data on housing starts for May ends the three-month slide in single-family starts, which are key to a healthy housing supply.

Initial and continuing jobless claims from the Department of Labor say a lot about the vitality of the labor market. Right now, they’re saying that although it’s still healthy, signs of fatigue are showing. Rising continuing claims are telling us that the time it takes to find a new job after a layoff is getting longer. I’ll be watching to see whether these weekly reads on the job market continue to edge higher.

Thursday: Markets and federal government offices are closed for Juneteenth National Independence Day.