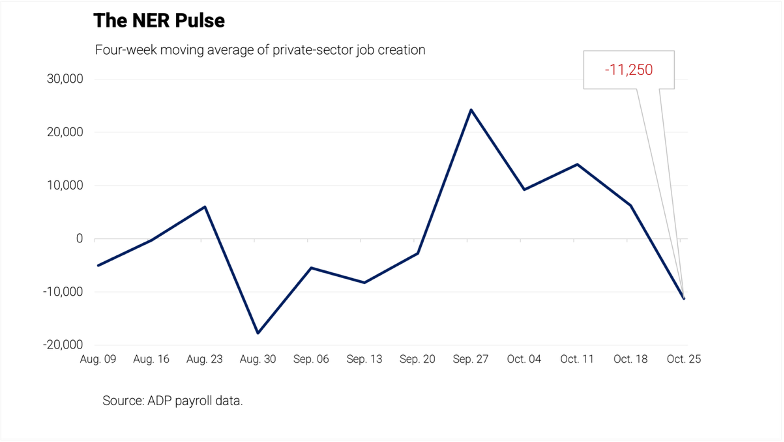

For the four weeks ending Oct. 25, 2025, private employers shed an average of 11,250 jobs a week, suggesting that the labor market struggled to produce jobs consistently during the second half of the month. These numbers are preliminary and could change as new data is added.

Three times a month, Main Street Macro releases the NER Pulse, an estimate of the week-over-week change in employment based on a four-week moving average. These releases are seasonally adjusted and have a two-week lag to allow for more complete and accurate estimates of real-time employment trends. At the beginning of each month, we publish the National Employment Report, which is built on a reference week that includes the 12th day of the month. We do not publish the NER Pulse during NER release weeks.

How slow is too slow?

Last week, The ADP National Employment Report showed that job growth had resumed in October after a two-month downturn, with private-sector employers adding 42,000 jobs.

The gain was welcome, but it wasn’t broad-based. Education and healthcare, and trade, transportation, and utilities led the growth. For the third straight month, employers shed jobs in professional business services, information, and leisure and hospitality.

However limited, October’s reading was still positive, to the relief of many economists and investors. Among these market-watchers, there’s growing sentiment that job growth will remain slow for the indefinite future due to a reduced demand for and short supply of workers.

So, how slow is too slow?

To answer that question, let’s look back at the year-over-year change in annual employment. I’ll focus on March data, because that’s the month we benchmark the NER to the federal government’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. March is when the NER most closely aligns with the population of U.S. workers.

Between 2010 and 2019, private employment grew by about 2 percent a year. But in 2020, with the start of the coronavirus pandemic, those job gains spiraled into losses. Private employment fell by 4.3 percent year over year as companies shed workers.

Hiring spun back in 2022, rising 5.7 percent. And in March 2023 delivered a comfortable year-over-year job growth of 2.6 percent.

Since that pandemic pirouette, private employers have settled into annualized hiring increases of about 1 percent, slower than the pace of growth recorded before 2020.

Is this the new normal? The Bureau of Labor Statistics seems to think so. It’s annual employment projections, released in August, shows total private- and public-sector employment growing by only 3.1 percent between 2024 and 2034, down from the 13 pace of growth we recorded between 2014 and 2024.

That means U.S. employment is likely to grow by just 0.3 percent each year over the next decade, a big step down from the already sluggish 1 percent we’ve averaged over the past two years.

My take

With labor supply and demand both slowing, economists are on the lookout for a new break-even rate. That’s the minimum number of jobs the economy needs to add each month to keep the unemployment rate steady.

But over the next decade, it will be difficult to find and maintain a balance in the labor market.

Between 2010 and 2019, employment growth was steady. Demographic and technological change has disrupted that constant.

Retirees are growing in number and the population growth of prime-age workers, people between 25 and 54, is slowing. New developments in artificial intelligence are changing the workplace.

The aging U.S. population will give health-care employment a consistent boost. Job growth in other sectors will depend on short-term demand fluctuations that are difficult to forecast in the presence of labor-changing technological advancements.

Not only is the pace of employment growth shifting lower, it’s doing so in a jagged path across occupations, industries, and geographies. Going forward, instead of being a stable constant, the break-even rate more likely will be constantly moving.

So, how slow is too slow? That will be an open question for years to come.

The week ahead

This would have been a data-filled week. With the ongoing government shutdown, we’ll miss a fresh read on inflation.

Wednesday: ADP Research will release an analysis showing that nearly 2 in 3 U.S. workers say they’re living paycheck to paycheck. That number is even higher among repetitive task workers, many of whom are employed in hospitality, transportation, or retail jobs characterized by lower pay, fewer benefits, and limited scheduling flexibility.

Thursday: We’re unlikely to get a fresh read on inflation for October. The Consumer Price Index, which is built on surveys and interviews, has been interrupted by the federal government shutdown. In the labor market, states are still delivering fluid but incomplete data on initial jobless claims, which have been signaling a low level of layoffs.

Friday: The Producer Price Index, commonly seen as an early indicator of consumer inflation to come, also is unlikely to publish week. Also missing will be Census Bureau retail sales data, a historically dependable indicator of consumer health.

ICYMI: Last week, an ADP Research report on the democratization of long-distance work showed that the practice of long-distance work, once the purview of only the largest companies, has become an important strategy for employers of all sizes, unlocking opportunities that can’t be ignored.

5 min

5 min